Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is one of classical music’s most famous openings. It begins with a distinctive four-note “short-short-short-long” motif. But what do the starting notes signify? Is it a thunderclap – or fate, knocking at the door? Perhaps “Oppenheimer-the movie” mirrors this dilemma and oscillates between the two.

It has been 10 days since Christopher Nolan’s latest creation “Oppenheimer” released in the theatres and 9 days (yes, I am counting) since I had the good fortune of experiencing it on the big screen and I have been contemplating about the director’s vision ever since , having made the exception of booking the ticket two weeks in advance for the first time in my life. What I initially thought would be a review of a 3-hour long biopic has instead in my mind turned into a more complex deliberation on the vortex of power vis-à-vis science. In three words, I describe this latest cinematic masterpiece as a “Triumph of Intellect”.

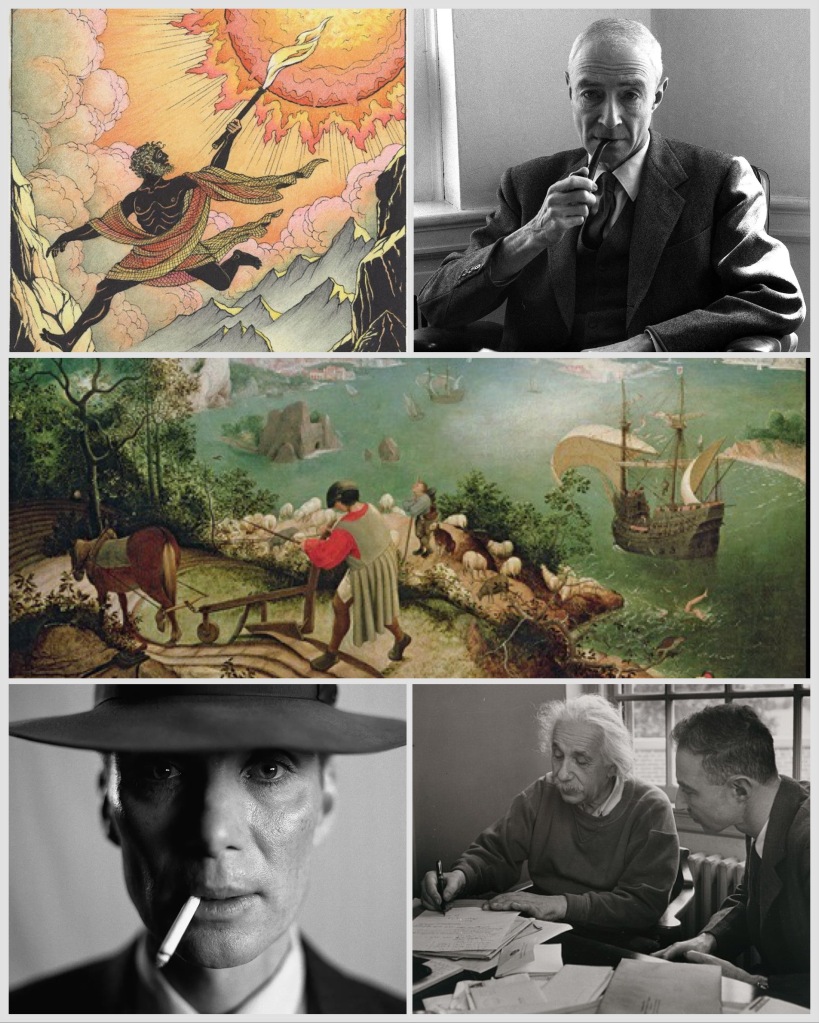

At the very beginning of the movie, two sequences play out which essentially lay bare the tone and tenor of what is to come ahead. And it is only much later while brooding about the movie that I realized the immense significance of these two sequences. Nolan is a wizard of reverse storytelling (remember Memento) and with Oppenheimer, the director plays with the timelines from the very first shot of the movie as Nolan surreptitiously interplays the ART of CINEMA with THEORETICAL PHYSICS. Along one timeline — in colour, with opening text reading “FISSION” — runs the story of Oppenheimer (an incredible Cillian Murphy), spanning his youthful forays into theoretical physics at European universities, through his years at Berkeley, his dabbling in left-wing politics, his affair with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh) and eventual marriage to Kitty (Emily Blunt), and his appointment by Gen. Leslie Groves (Matt Damon) to run the ultra-secretive Manhattan Project at Los Alamos. Through timeline jumps, we start to fill out a picture of what would happen to him after — in particular, an older Oppenheimer being investigated by a government commission regarding his ties to communists. Meanwhile, in a second track, we are witnessing — for reasons that do not become obvious for a while — an agitated Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), who is trying to get approved by the Senate as commerce secretary and isn’t quite sure why he’s meeting with resistance. This section is in black and white, and labeled “FUSION.”

Those labels are worth keeping in mind, because when at Los Alamos the Hungarian physicist Edward Teller (Benny Safdie) describes his idea for a hydrogen bomb — and someone later describes it as not a weapon of mass destruction, but a weapon of mass genocide — we suddenly learn the difference between fission and fusion. Fission, which splits the nucleus of an atom into two lighter nuclei, unleashes enormous power, capable of leveling Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But fusion, which combines two light nuclei into one, unleashes far more energy and can level, in a sense, the world.

OPPENHEIMER would have been a daunting subject for any filmmaker. A public intellectual with a flair for the dramatic, he directed the top-secret lab at Los Alamos, New Mexico, taking the atomic bomb from theoretical possibility to terrifying reality in an impossibly short timeline. Later he emerged as a kind of philosopher king of the postwar nuclear era, publicly opposing the development of the hydrogen bomb and becoming a symbol both of America’s technological and scientific might and of its conscience. That stance made Oppenheimer a target in the McCarthy era, spurring his enemies to paint him as a Communist sympathizer. He was stripped of his security clearance during a 1954 hearing convened by the Atomic Energy Commission. He lived the rest of his life diminished, and died at 62 in 1967, in Princeton, New Jersey. A life of triumph and tragedy, in equal measures, similar to PROMETHEUS in Greek mythology, who is best known for defying the Olympian gods by stealing fire from them and giving it to humanity in the form of technology, knowledge, and more generally, civilization, someone who represented human striving (particularly the quest for scientific knowledge) and the risk of overreaching or unintended consequences, embodying the lone genius whose efforts to improve human existence could also result in tragedy.

About a minute into Oppenheimer, it becomes obvious why Christopher Nolan wanted to tackle the project. His subject, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb,” was a theoretical physicist, a man who obsessed over the building blocks of the universe. He flings crystal goblets into corners to observe how they shatter and flirts with women by telling the scientific reasons his own matter won’t just pass through theirs. He dreams of particles and stars and fire; he becomes transfixed by water smacking the surface of puddles. Stoic in his decisions , a polyglot poet who lives in the contradictions, Oppenheimer is a man who delights in paradoxes; at his first encounter with a bewildered Berkeley pupil, he demands to know how light can be both a wave and a particle, and then proceeds, with gusto, to explain.

Nolan seems engaged in a long-running investigation of theoretical physics. He discerns some link between the cold material fabric of the universe — things like time, space, matter, death, eternity — and the more metaphysical meanings of human existence: love, identity, memory, and grief. Often, he weaves together emotion and science, then pulls some threads from ancient myth through the fabric to remind us these are eternal questions. From Memento to Inception, Interstellar to Dunkirk, The Prestige to Tenet, Nolan’s movies leverage Cinema as a Science (images, sound, time, chemicals on celluloid) to confront the tangible with the intangible. The man’s brain is a marvel. His craving for perfection led him to ditch CGI and use traditional graphics to recreate the visualization of atomic behavior and extreme beauty and terror of the trinity test.

Oppenheimer did not regret what he did at Los Alamos; he understood that you cannot stop curious human beings from discovering the physical world around them. Sadly, Oppenheimer’s life story is relevant to our current political predicaments. Oppenheimer was destroyed by a political movement characterized by rank know-nothing, anti-intellectual, xenophobic demagogues. His downfall reminds one of the “Fall of ICARUS” : a Greek parable on human aspiration. Daedalus and his son, Icarus, were imprisoned on the island of Crete. Daedalus created wings to fly away. Icarus, ambitiously, flew too near the sun. The wax holding his wings together melted and he plunged into the sea and drowned. The Oppenheimer case sent a warning to all scientists not to stand up in the political arena as public intellectuals. Cut to present day, we stand on the cusp of another technological revolution in which artificial intelligence will transform how we live and work, and yet we are not yet having the kind of informed civil discourse with its innovators that could help us to make wise policy decisions on its regulation.

The greatest scientific minds in the world are public intellectuals who respond to a higher calling that transcends the paradigms of nations and geo-politics. Oppenheimer belonged to that category, a man of science who was in equal measures a polyglot, a philosopher and a theoretical physicist. You can see this in the repetition of the line from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds,” which Oppenheimer reportedly quoted after the test bomb, nicknamed Trinity, successfully detonated in the desert and showed the scientists and politicians of what it was capable. The moment, at least for Oppenheimer, is a visceral punch, an acknowledgment that with this great invention comes the ability to destroy humankind. Something has been unleashed (a chain reaction) that cannot be pushed back into the bottle.

The movie has not entirely figured him out, and history has not either, but there is no doubt he’s a figure of towering importance. In Oppenheimer, Nolan focuses his lens on power — the kind that split atoms produce, the kind that countries wield, the kind that men crave. Nolan’s Oppenheimer barely qualifies as a biopic, at least not the thudding Hollywood variety. Instead, it is a movie — a virtuoso, among his best — investigating the nature of power: how it is created, how it is kept in balance, and how it leads people into murky moral quandaries that refuse simplistic answers.

Happy Birthday, Mr. Nolan. We are lucky to watch you magically wield your craft as one of the modern masters of avant-garde cinema.