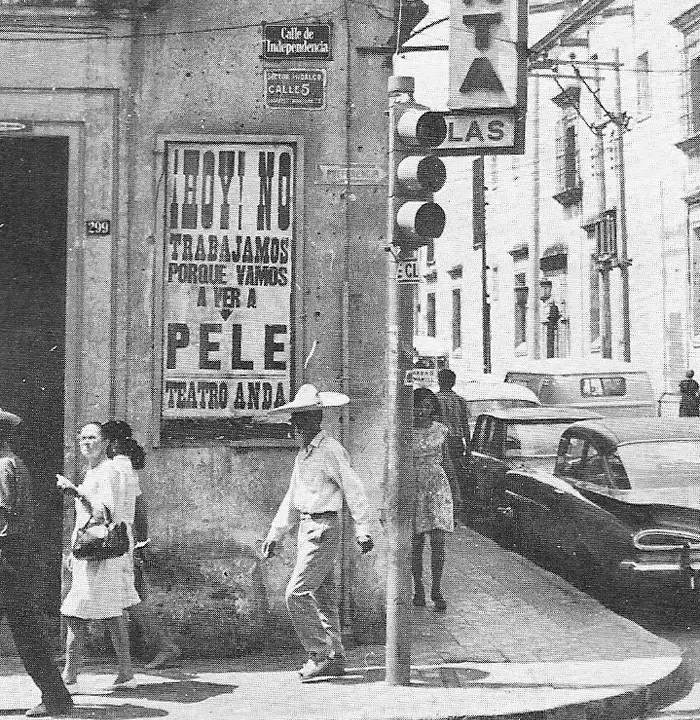

Place: Guadalajara, Mexico

Occasion: 1970 Football World Cup

At Indendencia Street, in downtown Guadalajara, a sign was placed on the ANDA Theatre: “Hoje! Não trabalhamos porque vamos ver Pelé”, translated “Today! We don’t work because we’re going to see Pelé”.

At the end of the 1970 World Cup, the English newspaper The Sunday Times published a historic headline: “How do you spell Pelé? GOD”. In the glorious championship in Mexico, Pelé showed Brazilian football to the world, like no one else, and made a city stop working to watch him. In 2019, the official page of Santos, the club where the player made history, joked with the photo: “ Work dignifies the man, but seeing Pelé on the field dignifies him even more. Privileged are those who had the chance to live this unforgettable experience”.

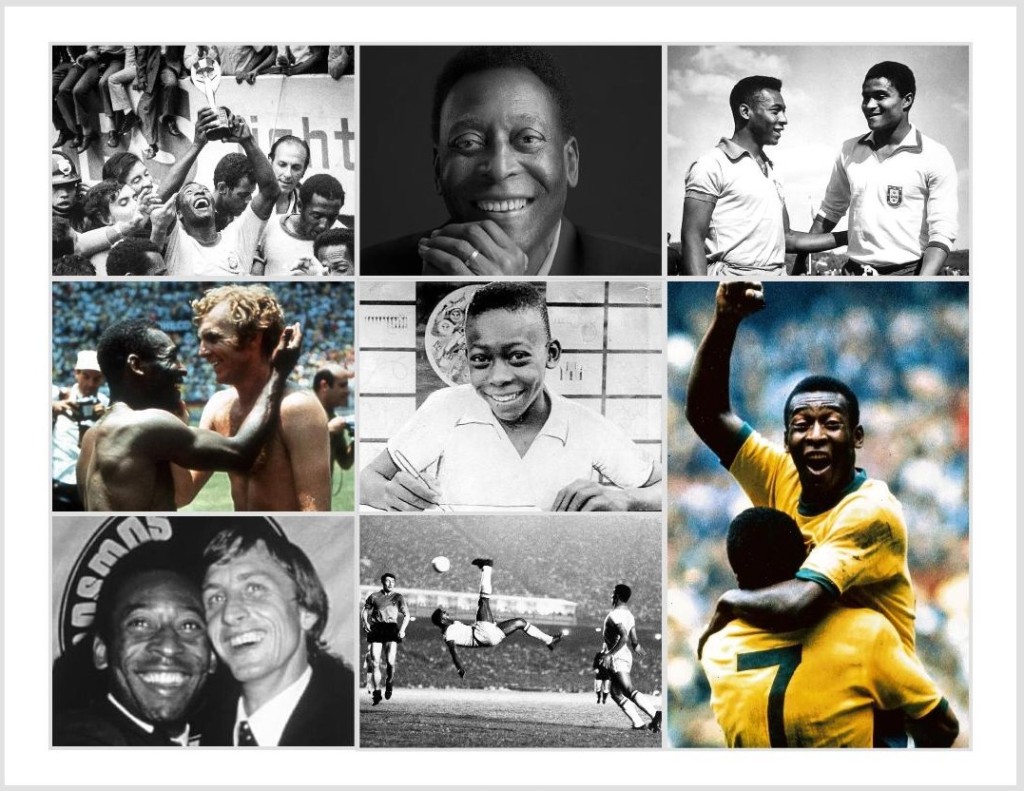

Pelé was one of the first global sporting superstars who transcended continents, admired for his wizardry and sometimes criticized for his political stance, or the lack of it. Pelé’s greatness can be measured by the simple fact that he could make football a spectacle of natural grace and beauty when he missed as much as when he scored. He was the national treasure who once managed to bring about a 48-hour ceasefire between two warring factions during the Nigerian civil war in the 1960s, just so they could watch Pelé play in an exhibition game in Lagos. He was also the person who played a big part in Calcutta hosting him and the New York Cosmos during its tour of Asia in 1977. Pelé played in that game against Mohun Bagan at the Eden Gardens for about half an hour, in the winter of his career and far from his best, but still a turnout of 80,000 mesmerized.

Pelé suffered World Cup disappointments too, none more than when he was brutally kicked out of the competition in England in 1966. He left the scene of the 3-1 defeat by Portugal at Goodison Park draped in a blanket after a succession of fouls that left him limping on one leg, with his right knee heavily bandaged. That knee injury was caused by earlier savage challenges in Brazil’s first game against Bulgaria and Pelé was so disgusted by his treatment that he vowed never to play in another World Cup – a decision the game was grateful he later reversed.

Brazil’s 1970 World Cup win was the pinnacle of Pelé ‘s career. He was the focal point of a dream team that has become enshrined in the game’s history. Pelé may have been the headline act but he was accompanied by names such as Rivelino, Jairzinho, Tostao and Gerson, as well as the great captain and leader Carlos Alberto. Testimony to Pelé ‘s brilliance are two occasions in the 1970 Mexico World Cup when he failed to score – and yet are used to this day as prime exhibits of the skill, power, elegance and mental speed and agility that mark him out as arguably the greatest to have ever graced the game. The first came in Brazil’s opening group game against Czechoslovakia when Pelé , from several yards inside the centre circle in his own half, received the ball languidly then spotted keeper Ivo Viktor off his line. In an elegant, instinctive swing of his right boot, he sent the ball in a high arc towards goal, landing inches wide, with the panicking Viktor making a scrambling retreat before the relief of realising he had not been embarrassed by Pelé ‘s genius. Fast forward to the semi-final against Uruguay, again in Guadalajara, when Pelé raced at full speed on to Tostao’s pass, yet still had the presence of mind to run past keeper Ladislao Mazurkiewicz, also allowing the ball to run past the pair. The keeper had been sold perhaps the greatest dummy in World Cup history. Sadly, the angle was subsequently too tight for Pelé to score but the moment is still replayed whenever World Cups are relived and as the late, great BBC commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme, probably taken as much by surprise as Mazurkiewicz, said in that wonderful moment: “What genius. Incredible.”

Brazil, in 1888, was the last Western country to abolish slavery, and Pelé was born just 52 years later, a poor Black child who started out life shining shoes. Edson Arantes do Nascimento was born on Oct. 23, 1940, in Três Corações, a tiny rural town in the state of Minas Gerais. His parents named him Edson in tribute to Thomas Edison. (Electricity had come to the town shortly before Pelé was born.) When he was about 7, he began shining shoes at the local railway station to supplement the family’s income. One of Pelé’s earliest memories was of seeing his father, while listening to the radio, cry when Brazil lost to Uruguay, 2-1, in the deciding match of the 1950 World Cup in Rio de Janeiro. The game is still remembered as a national calamity. Pelé recalled telling his father that he would one day grow up to win the World Cup for Brazil. And he did in 1958. He had become such a hero that, in 1961, to ward off European teams eager to buy his contract rights, the Brazilian government passed a resolution declaring him a non-exportable national treasure. I am not joking. You can check the records !!! When Pelé was about to retire from Santos in the early 1970s, Henry A. Kissinger, the United States secretary of state at the time, wrote to the Brazilian government asking it to release Pelé to play in the United States as a way to help promote soccer, and Brazil, in America.

In his 21-year career, Pelé — born Edson Arantes do Nascimento — scored 1,283 goals in 1,367 professional matches, including 77 goals for the Brazilian national team. Many of those goals became legendary, but Pelé’s influence on the sport went well beyond scoring. He helped create and promote what he later called “o jogo bonito” — the beautiful game — a style that valued clever ball control, inventive pinpoint passing and a voracious appetite for attacking. Pelé not only played it better than anyone; he also championed it around the world. Among his athletic assets was a remarkable center of gravity; as he ran, swerved, sprinted or backpedalled, his midriff seemed never to move, while his hips and his upper body swiveled around it. He could accelerate, decelerate or pivot in a flash. Off-balance or not, he could lash the ball accurately with either foot. Relatively small, at 5 feet 8 inches, he could nevertheless leap exceptionally high, often seeming to hang in the air to put power behind a header.

How does one define an ICON? A person or thing regarded as a representative symbol or as worthy of veneration They say Muhammad Ali was arguably the greatest sports personality of all time. Pelé was that and more. In his pomp, Pelé was Ali from the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’, Jesse Owens in Berlin Olympics. He was Rafael Nadal at Roland Garros, Tiger Woods at Augusta, Usain Bolt and Michael Phelps in Beijing, London and Rio. All rolled into one, many times over!! Maybe it’s best to let pop-culture icon Andy Warhol define Pelé’s legacy in his own inimitable fashion,

“Pelé is one of the few who contradicted my theory,” “Instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries.”